Why betting on NFTs isn’t a bet on a dystopian future

Plus, why not all types of discrimination are bad

“You like NFTs? You must be a loser”

“You don’t get it”

“I do get it. You like the metaverse, I like the universe. You like digital goods, I like physical goods. We are not the same”

The root of NFT criticism

One of the most touted theses for NFTs is that because we are spending more time online every year, we need to own more of our “digital stuff”. Daily screen time averages 7 hours and counting globally. The more time we spend on screens, the more that our economy will shift digitally to monetize our attention.

We’ve already seen this happen over the past two decades. Digital things in some cases had already become more valuable than their physical counterpart long before NFTs. For example, the domain name Privatejet.com sold for more than most private aircrafts are worth.

In a previous newsletter, I talked about how in some ways, the metaverse is already here (yes, I just linked my own article… that’s show biz baby). The basic thesis of that newsletter was that when our digital and physical worlds collide, and it’s hard to decipher whether culture is originating digitally or physically, that’s a sort of metaverse.

But I speak to you today to take a stand, or I should say FROM the stand, defending myself from the constant criticisms of my peers who exclaim to me “you want people to spend more time on their screens and you build things that facilitate that behavior… we shouldn’t all be misanthropes!”

They continue down the path of explaining to me that it’s the metaverse’s fault that American Millennials and Gen Z are in decline by way of:

Being poorer than expected: millennials make up the largest percentage of the workforce, but only control 5.9% of the wealth.

Being less sexually active: Young adults are having less sex (especially casual sex)

Being sadder than ever: young adults are are unhappier than at any time since data collection began.

Ok, boomer, how does it feel to have 51% of the wealth while us millennials have one tenth of that? Prettttttty, prettttty, pretty good indeed.

From a “metaverse sucks” point of view, the above bullet points all boil down to the fact that our screens make us care less about who we are in the real world. Who needs sex when you have digital first relationships and VR pornography? Who needs wealth when all you need is a comfy chair and a big monitor? Sad, sad indeed.

It’s really not much different than the last decade’s criticisms of Instagram: people aim to be cool online to receive the admiration they crave, even when that admiration happens IRL. Just Do It → Just Take a Picture of It.

I had a conversation with a friend of mine last week who argued that by nature of working in technology, we have a responsibility to build things that make the world a more beautiful place, the real world, the one we walk around in. I agree with that sentiment. We have a responsibility to fight decline in our civilization if we believe it to be happening.

So, I had to ask the question: are NFTs a bet on a dystopian future that I don’t want to be a part of? If they are, we at En Passant Digital have to question our decision to build NFTs for companies.

To get to the bottom of this, I thought back to what intrigued me about NFTs in the first place. To understand this, we have to rewind to my college days to a class called ECON 3012, Microeconomics, Consumer choice and firm behavior from the fundamentals of preference and production theory.

Yes, it sounds like a bore, but trust me, it gets fun (fun is relative).

“I am like any other man, all I do is supply a demand” - Al Capone

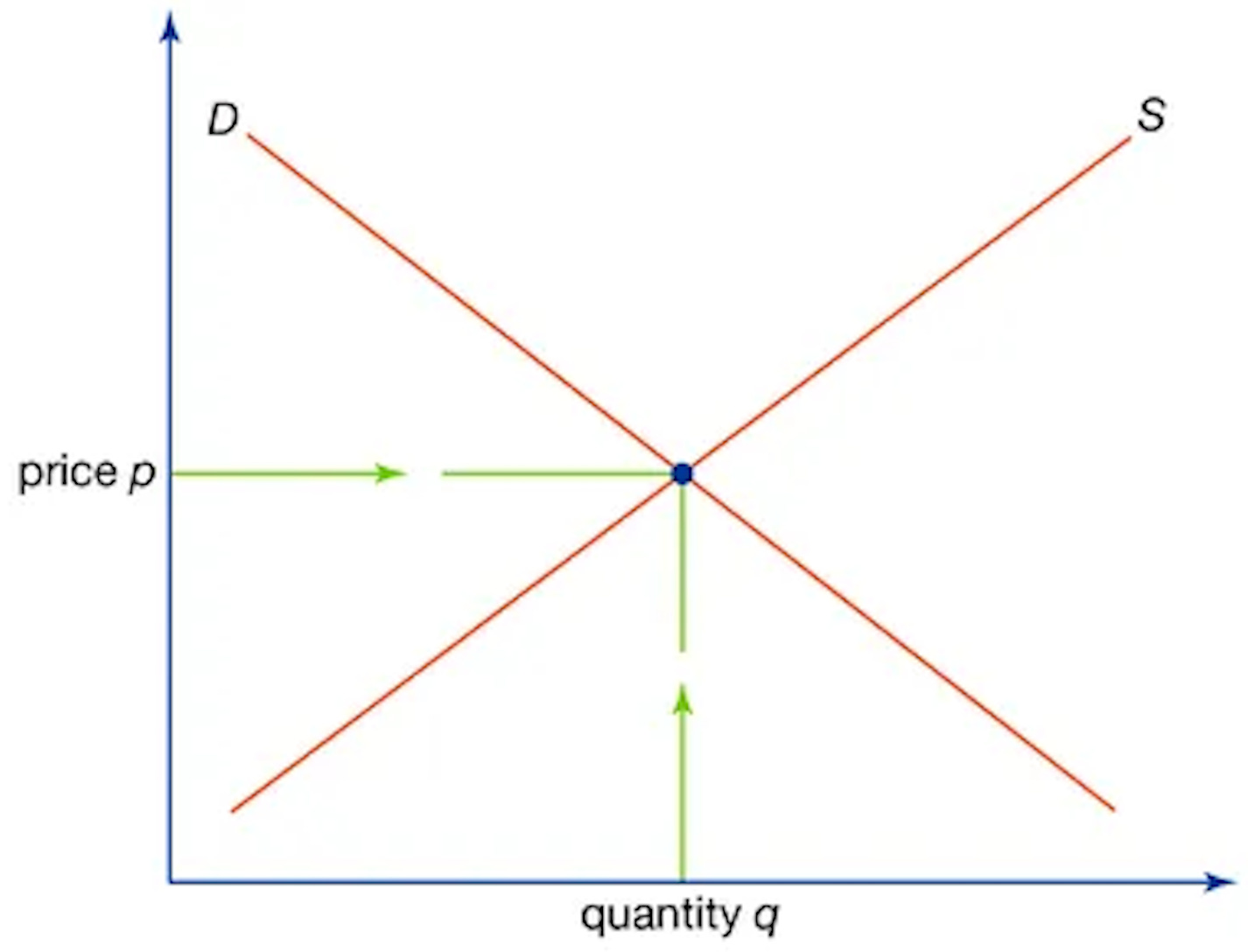

As Dad used to always say, it can all be boiled down to supply and demand. Graphically, we portray that as:

Encyclopedia Britannica

In layman's terms, this means where those two lines intersect, the price the company charges the customer will be “price p” and the quantity they will produce is “quantity q”. To use a concrete example, a t-shirt store will charge $20 / shirt and there is demand for 1000 shirts / year at the $20 price point, equating to the $20,000 / year in revenue, which is the most money that the store can make under these market conditions.

The company prices their product and they sell it to whoever will buy it at that price. So far so good.

While this is a perfectly fine way to go about business, businesses always have to question if they are pricing their product optimally. This hypothetical t-shirt store has to ask the basic question: if we price our shirts at $25, can we sell more than 800 shirts (800 shirts @ $25 is also $20,000 / year)? If the answer is yes, they should raise prices to $25 / shirt.

This world I have described is the one we live in, a world without price discrimination, which would allow businesses to charge customers different prices for the same good. This is because the company has to charge everyone the same price even when some customers are actually willing to pay more than the price they are charging.

Capturing consumer surplus

This graph shows the amount of money left on the table by the company by not being able to charge each customer their maximum willingness to pay:

The blue triangle represents the money the company doesn’t receive because they have to charge everyone the same price, P1, for their goods / service. Technically, if you could price discriminate, there are prices higher than P1 that can be charged to avid customers that can afford it.

What’s funny about consumer surplus (remember, fun is relative) is that it’s so obviously impossible for every customer to walk into your store and for the business to be able to think “that person is willing to pay $45 for this t-shirt” and charge them that price at the register. We make a lot of assumptions when we study economics, and this assumption of not being able to price discriminate makes sense. But, assumptions don’t always hold true.

Companies have found ways to charge different customers different prices, but the offering has to be different so they can suss out who is willing to pay more and who can’t. Going back to the t-shirt example, this t-shirt brand can release a limited-edition silk t-shirt and charge $50. No one would argue this is bad for the consumer - they are getting what they want even if they have to pay more for it.

In tech, we call this “versioning” or “tiering”, providing different versions of service for different price points.

In other words, passionate fans of a brand / product / service can pay more than less passionate ones because they care more and can afford to do so. We know this type of avid fandom applies to a large subset of the population.

The Power of Fandom report from Troika indicates that “49% percent of the fandom we captured in the quantitative survey fell at the highest levels, with fans describing themselves as being ‘as avid as a fan can be.’”

To capture the consumer surplus from avid fandom, different industries have different methodologies. I described one simple version of “versioning” in the t-shirt example, but to fully understand the case of getting back to why I led you down this economics rabbit hole, we have to look at price discrimination opportunities in digital industries.

NFTs solve this

Take film, which, before streaming, allowed film creators to harness different windows of distribution to allow fans to make the choice of:

Going to see the film in theaters

Buying the film on VHS / DVD

Subscribe to a TV service like HBO which eventually shows the film

These windows all occurred at different times and were delivered at different price points. The most avid fan might have seen the film in theaters and then bought it on DVD, while the least avid fan might have subscribed to HBO and waited to see the movie. In a world of streaming services, those windows and discrepancies no longer exist. It’s harder to capture the surplus when there’s only one viewing option.

In other words, both the superfan and the casual fan simply click “watch” on Netflix, which leaves a lot of money on the table. Sure, films will create extensions of popular franchises by selling merchandise or extension experiences in extreme cases (e.g., Spiderman the video game), but this only works for major blockbuster franchises and doesn’t provide a solution for the smaller guys to capture their consumer surplus.

In crypto-twitter-speak, “NFTs solve this”.

NFTs allow films (or any brand) to mine the IP they have created for maximum value, allowing the superfan to pay more than the casual fan, capturing the lost consumer surplus. This is also better for the consumer, because they can buy more of what they want and less of what they don’t.

Using the film example, this allows us to do things like we did with the Zero Contact Film NFTs, where the most avid superfans could buy an NFT that allowed them reshoot themselves into an Anthony Hopkins film, while the less passionate fans could buy and sell access to stream the film. Still, these less passionate fans care about the film, as it’s completely unbundled from other film titles, so their decision to watch this specific title is intentional, but they are less passionate and pay a lower price than the superfans who bought the highest tiered NFTs.

Ben Thompson famously saw this trend in 2017, calling it “The Great Unbundling.” Summed up, we want more of the stuff we like and less of the stuff we don’t.

Here’s the takeaway: NFTs bring scarcity to industries that can’t offer scarcity in their current digital-first state, and that scarcity can be used to capture lost consumer surplus.

De gustibus non est disputandun

Nothing about being a hyper-capitalist is dystopian, it’s just good business. Nothing about this is a VR-goggle-drooling-asexual-economic-declining future, it’s actually the opposite. By giving fans, another word for consumers, exactly what they want, businesses will thrive (even non-traditional creative industries as opposed to traditional labor), allowing consumers to maximize their happiness.

Want to increase the earning potential of young adults? Give them a way to earn doing what they love. The film example from above can be applied to almost every industry. Digital scarcity, when wielded correctly, allows for hyper-efficient monetization mechanisms.

Want to encourage young adults to go out and meet IRL as opposed to digital-only relationships?

Allow them to work in a field they are most passionate about and make real money doing it.

More wealth → more freedom → the ability to close the computer at 8PM and go on a date. Whether they choose to do that or not is up to them. If I’ve learned anything in this life, it can be boiled down to de gustibus non est disputandum, which is Latin for “in matters of taste, there can be no disputes.”

NFTs are certainly not to blame for people’s preferences in behavior. If people want to spend all their waking hours sucked into the “metaverse vortex”, they’ll do it with or without NFTs.

Most importantly, the way we believe NFTs can be used over the next decade, they can encourage young adults to create things they want to create because of their ability to capture previously unobtainable consumer surplus, leading to happier and healthier individuals.

Well, I can’t speak for everybody, but that’s what we’re building towards at En Passant Digital.

Talk to us!

If you are looking for an expert* opinion on your NFT project, or want to talk generally about the market, please reach out for a no-obligations 20 minute phone call. We have a number of technology partners at En Passant Digital that help us bring your legacy IP to the blockchain.

Email: bryce@enpassantdigital.com

*Anyone who claims to be an expert is a charlatan. They are generally snake-oil salesmen who probably also told you to buy OneCoin. From the last 4 years of our experience, we’ve realized that there are no experts in the space, as it changes by the second.

About the author: Bryce Baker is the co-founder of En Passant Digital, an NFT-focused agency bringing innovative market guidance and strategy to top-tier brands & celebrities.

Our other co-founder, John Tabatabai, has led investments for Crypto VCs and consulted for projects across the NFT space. He recently had an active role in advising, designing and creating the mechanics and infrastructure for the famous B20s, aiding in creating more than $250,000,000 of value in less than 45 days.

Great article, Bryce. 👏 👏

Kind of unpacks the famous Charlie Munger quote, “show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome”